No:

Protect the Homeland.

“Morning Pledge” by Thomas Kinkade pic.twitter.com/JLs26R3VlO— Homeland Security (@DHSgov) July 1, 2025

No. No. No. No. No.

Here is my favorite Thomas Kinkade story:

And then there is Kinkade’s proclivity for “ritual territory marking,” as he called it, which allegedly manifested itself in the late 1990s outside the Disneyland Hotel in Anaheim.

“This one’s for you, Walt,” the artist quipped late one night as he urinated on a Winnie the Pooh figure, said Terry Sheppard, a former vice president for Kinkade’s company, in an interview.

So it seems that Kinkade (d. 2012, age 54) missed his calling as a drip painter:

[KInkade] was given to visual tricks like infusing his paintings with light emanating from every possible surface – typically trees, fields and barns in rustic landscapes – and hiding the names of family members in the scenery. The artistic elite despised him, but U.S. consumers were so entranced with his charming vision they paid $100 million annually to purchase his works. Kinkade’s paintings are rumored to hang in 10 million homes across the nation, leading his website to proclaim him the “most-collected living artist of his time.”

To be fair, Kinkade wasn’t sponsored by the spooks, either. In fact, he was prolific, and his paintings (for some definition of “painting,” of course) became unbiquitous:

Rather than sell originals, Kinkade had his work reprinted on paper, canvas and all manner of consumer goods including mouse mats, china dishes, La-Z Boy sofas and bed linen. These were mostly sold via the QVC shopping channel and a network of franchised Thomas Kinkade Galleries, usually located in shopping malls, numbering hundreds at the peak of his success. Accessibility was key. You didn’t need to be a rich gallery-goer to acquire one of his works — just to have a few dollars and a Kinkade concession nearby.

Most would classify KInkade’s art as kitsch, and Kinkade as a kitschmeister (“I know it when I see it“[1].) Etymology is always fun and revealing:

According to Cǎlinescu (1987), it was in Munich between 1860 and 1880 that ‘kitsch’ entered the jargon of painters and art dealers as a synonym for “cheap artistic stuff” (p. 234). 1 Despite its rather recent appearance, etymology of the word kitsch still lies in the dark and has been subject to wildest speculation (Kluge and Seebold, 2011). 2 From his personal recollections, Avenarius (1920) reported that the German ‘Kitsch’ comes from a mispronunciation of the English ‘sketch’ that was widespread among artists who sold oil paintings of poor quality as souvenirs to Anglo-American tourists visiting Bavaria’s capital. Although Avenarius claimed to be an ear-witness in the case, his theory seems highly improbable….

That’s too bad, since one of the Academy’s indictments of Impressionists was that their paintings were mere “sketches,” without the finish of pompier art as demanded for display in the official Paris Salon.

…. as a typical German mispronunciation of ‘sketch’ [skɛtʃ] does not sound similar to ‘kitsch’ [kiʧ]. … According to Best (1985), the noun ‘Kitsch’ originates in Swabian dialect where it was used to designate scrap wood, flotsam, or crude wooden objects, while the corresponding verb ‘kitschen’ referred to peddling but also to carrying a heavy burden on one’s head or by means of a back-basket. Related expressions from Alsatian dialect (noun ‘Ketsch’; verb ‘ketschen’) support the hypothesis that the semantic field originally comprised the content of a peddler’s carrying frame (noun ‘Kitsch’) as well as the act of petty trading (verb ‘kitschen’). Apart from allocating the origins of the word kitsch to German dialects from the region where it first appeared in its modern sense, Best’s etymological theory also touches upon two influential socio-economic developments of the nineteenth century that have been regarded as prerequisites for kitsch production: Industrialization and universal literacy (Greenberg, 1939).

And indeed it might be fair to characterize Kinkade as a peddler of gimcracks. From the Washington Post:

“This is where I’m putting my retirement money,” says a woman in a brief but infuriating scene from the new documentary “Art for Everybody,” about the life and downfall of the enormously popular kitsch artist Thomas Kinkade….

If she did invest her life’s savings in Kinkade’s mass-produced art, which became wildly popular in the late 1990s and early 2000s, she is probably destitute today. The scene appears in the film just before the inevitable collapse of Kinkade’s company and ultimately his life, as the market for his work became saturated and he turned increasingly to alcohol and drugs for relief from whatever demons haunted him.

But wowsers, the scribes at WaPo sure hate the guy. I mean, “whatever demons”? The demons that haunted Kinkade were in fact real, as the very documentary revealed by Post shows:

What you might not know is that, just like Prince at Paisley Park, Kinkade had a vault at his Placerville, California home that contains 6,000 works that were never exhibited, never printed on a La-Z-Boy, never hung in the homes of the one in 20 Americans who he once boasted bought his work.

Now, his family has revealed those works, and opened up about the man behind the persona, in the revealing new documentary Art for Everybody.

Also in the documentary:

[Kinkade]said in a surprising audio recording, “I want to avoid painting silly and sweet pictures, charming pictures, happy pictures. I want to paint the truth, and the truth of this world is not happiness. The truth of this world is pain, and that’s the only truth.”

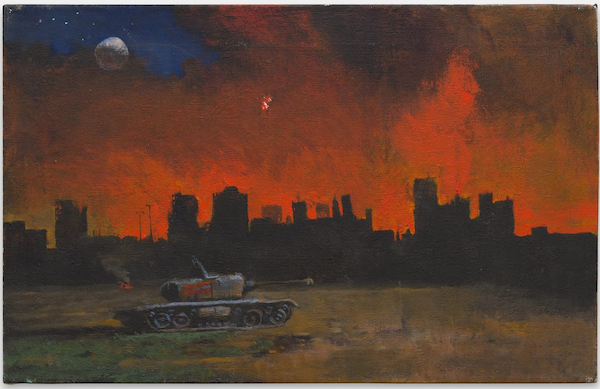

So, the painter of darkness, too:

For the record, I couldn’t disagree more with Kinkade; I would urge that Kinkade’s first claim — “the truth of this world is pain” — and his second claim — “that’s the only truth” — are both untrue. (Here, however, “I refute it thus”). More to the point, Kinkade enthusiasts disagree. The truth that they see is beauty. From a Pinterest board curated by Carol Mingus:

Meanwhile, the critics see something quite different:

“Thomas Kinkade’s style is illustrative saccharine fantasy rather than art with which you can connect at any meaningful level,” Charlotte Mullins, the author of A Little History of Art, tells the BBC.

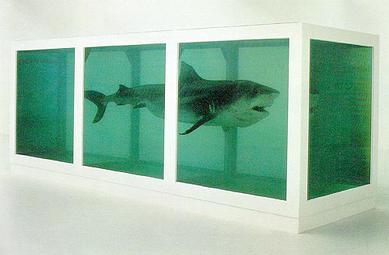

Where is this “meaningful level” of which Mullins speaks? Damien Hirst’s dead shark?

Jeff Koon’s balloon dogs?

(Now available as Bluetooth speaker lamps.)

A functional left would not be mocking Kinkade (and I confess I thought this would be an easy post to write; all I would have to do is write a little snark, done). A functional left would ask “Why do millions seek beauty in images of the past?”[2] Is the present that ugly? Given an answer — even if the answer to “why” were the all-purpose “racism”[3] — they would then ask “How can millions be brought to seek beauty in the future?” Corey Robin says somewhere that conservatism is “a meditation on lost power,” and Kinkade’s paintings of light are surely that, but how did such meditations become, well, hegemonic? Ten million homes is rather a lot….

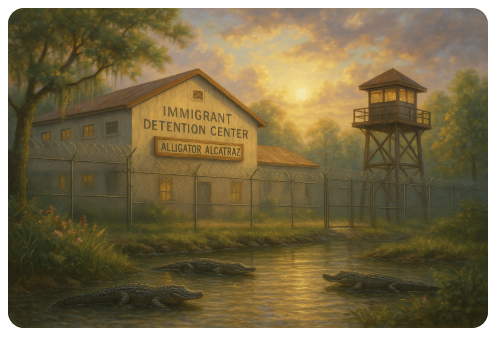

One thing — perhaps the one thing — ChatGPT is good for: producing instant parodies

fixed it for you. we’re not going backwards. we’re building forward. pic.twitter.com/l5J4npWLvg

— Izem Guendoud (@Izemthinks) July 1, 2025

Or:

Oh, we will, believe me. pic.twitter.com/8pWKAER0TG

— Wayne of the Wastes (@WayneOWastes) July 2, 2025

But I’m surprised that nobody’s thought to do this:

How secure is that homeland, really?

NOTES

[1] Some threads on X classify Kinkade’s art as fascist kitsch. That is, or ouht to be, a tough sell, because the Nazis passed an anti-kitsch law:

(Just because Hitler hated modern art doesn’t mean he loved kitsch.)

[2] Is a bad Monet (not Manet) really all that different from a “painting of light”? Surely there’s just a tinge of the saccharine in Monet? Who is also on coffee mugs everywhere?

[3] Apparently some Kinkade owners actually stick mini-lights through the canvas. This is much like the aesthetic of model railroading, where an aesthetic of “realism” is achieved with tiny details, like streetlamps that actually light up. I can grant that nostalgia for an imagined all-white, 50s-style past is a thing, but whatever’s going on with Kinkade devotees, their aesethetic is not evidently monocausal.

Comments

To give me a jigsaw puzzle of/with a Thomas Kinkade painting. His stuff is perfect for that.

Though I imagine I could undermine my own point by finding a jigsaw puzzle of “A Bar at the Folies-Bergère” or maybe even Olympia.

Add new comment

- Add new comment

- 16 views

I keep waiting for someone